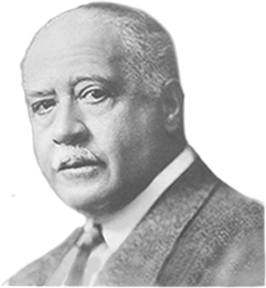

James Loeb

James Loeb gehört zu den eindrucksvollen Persönlichkeiten des 20. Jahrhunderts. Aus begüterter Familie stammend, lebte er für seine musischen Interessen und besaß eine herausragende Sammlung griechischer, etruskischer und römischer Kunstwerke, die heute in den Staatlichen Antikensammlungen München am Königsplatz aufbewahrt wird.

Loeb unterstützte aber auch zahllose Institutionen und Privatpersonen, ohne dies je öffentlich werden zu lassen. Große Teile seines Lebens verbrachte James Loeb auf dem von ihm gestalteten Gut Murnau-Hochried.